To forgive is one of life’s most difficult acts, but it can also be its most fulfilling. It lifts burdens, clears minds, and creates a sense of emotional and mental freedom like none other. Titus Kaphar’s Exhibiting Forgiveness represents an intersection of deeply personal narrative and an exploration of family, trauma, and reconciliation through both painting and film. This new body of work, displayed at Gagosian Beverly Hills invites viewers to witness the artist’s perspective through art as he grapples with the long-standing complexities of his relationship with his estranged father. The exhibition showcases 15 new paintings, which are pivotal to his feature film of the same name, a semi-autobiographical piece that intertwines his artistic processes with his life story.

Kaphar’s creation of both these projects started with an unexpected encounter. Upon visiting his grandmother’s house in Michigan with his family, he was met by his father, who had been absent for over 15 years. This surprise reunion stirred unresolved emotions from his past, leading him to reluctantly film his father and later create a short documentary, The Jerome Project, about their complicated relationship. However, the doc did not provide Kaphar with the closure or understanding he sought; it captured their dynamic, but not how they arrived at that point. “The 15 years of script that I had written in my head about what I was going to say to him when I saw him next just didn’t make any sense anymore,” he says.

Years passed, and Kaphar found himself wanting to communicate this experience to his two sons, who were approaching adulthood. This became the foundation for the film which tells the story of a Black artist, Tarrell Rodin, who is on the cusp of professional success when his father, La’Ron, re-enters his life, desperate to reconcile. Starring André Holland and John Earl Jelks, the narrative mirrors the artist’s own life, as Tarrell confronts the emotional and psychological scars of his past. In discussing the film, Kaphar explains, “I started this process because I wanted to find a way to communicate with my two sons about how different my life is from theirs.”

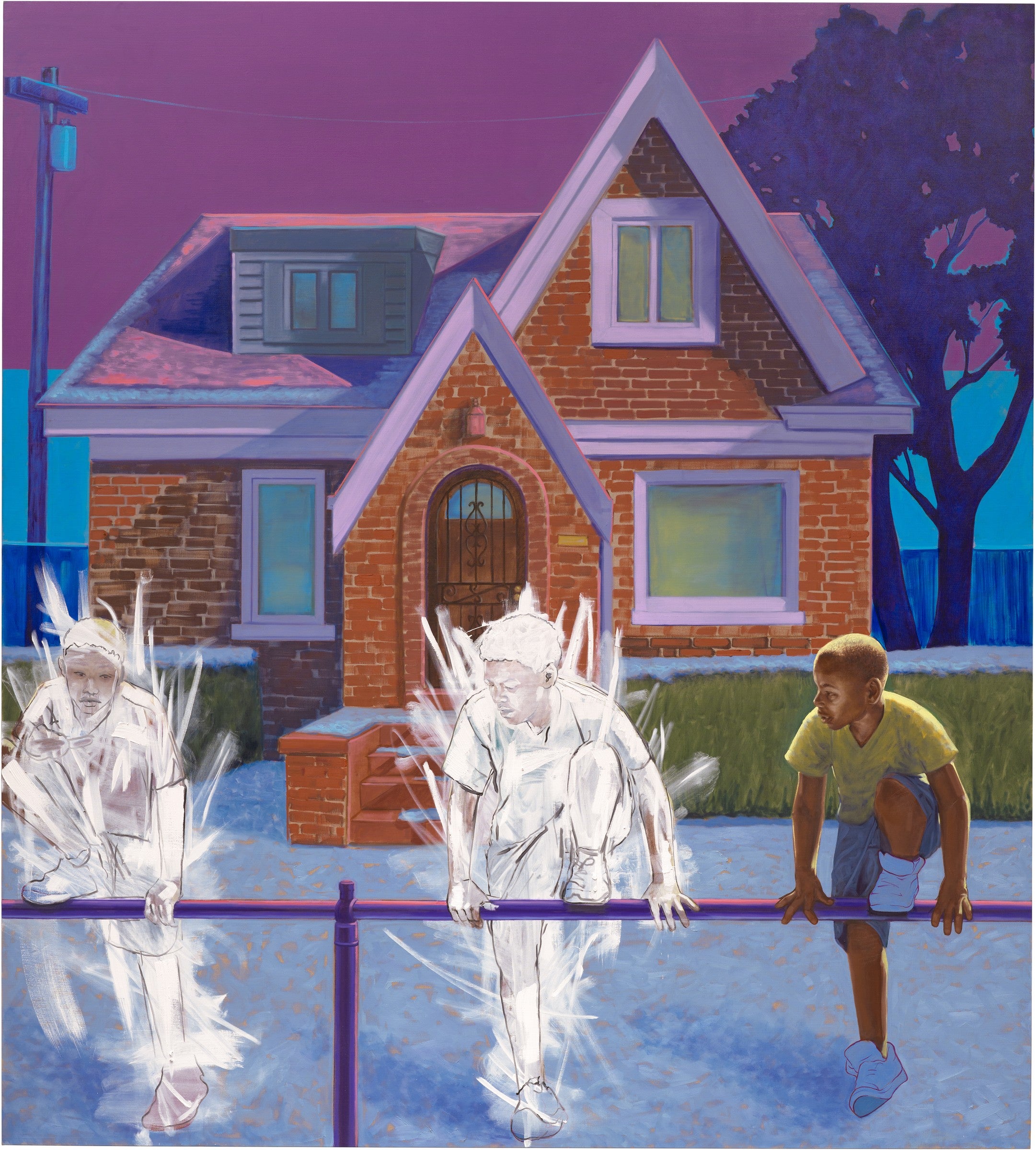

Exhibiting Forgiveness emerged as a visual counterpart to the film. They capture the essence of the film’s narrative and the emotional weight that underpins it. Each piece is filled with personal objects, neighborhood facades, and poignant portraits that reflect themes of absence, loss, and the burden of familial history. Kaphar’s mastery in combining traditional oil painting techniques with unconventional materials, such as gold leaf and tar, challenges viewers to confront the tensions between divine transcendence and the burdens of the past.

The striking interplay of color in his large-scale canvases conveys the vividness of memory, both painful and beautiful. For instance, in Bad memories more saturated than good ones (2023), Titus paints an overburdened truck, symbolizing childhood trauma. This heavy imagery resonates with the weight of carrying the past, a theme central to the film and the exhibition. The trucks and neighborhood homes depicted in his works become symbols of community, resilience, and the emotional baggage that must be navigated to move forward.

One of the most compelling paintings, For your prayer closet (2023), uses materials drawn from The Jerome Project. It symbolizes both transcendence and the darkness of familial wounds, tying into a climactic scene in the film where Tarrell reflects on his past. Kaphar’s creative decision to use the paintings as integral components of the film—physically moving them through on-screen space during flashback sequences—demonstrates how deeply intertwined the two art forms are. “If I have to make a bridge between those paintings and the film itself,” Kaphar states, “it is this conversation around absence. It’s this conversation around what should have been there and wasn’t there, and how do you tell the story when there are gaping holes in the narrative?”

Kaphar’s venture into filmmaking is a natural extension of his storytelling as a visual artist. He describes the process as part of his ongoing journey of exploring new mediums when the work demands it. “If you only know how to paint, then your creative and artistic outlet will only be paintings,” Titus says. “But if you are willing to learn new practices, then as they say, the sky’s the limit.” This philosophy drove him to embrace filmmaking, allowing him to tell a story that could not be fully conveyed through paint alone.

At the heart of both the exhibition and the film is the concept of forgiveness. Kaphar is clear that forgiveness is not about a neatly wrapped, happy ending. “Movies really want to give you a clean ending…when sometimes the reality is what we have is not a happy ending as much as a hopeful beginning,” he reflected. His personal journey with his father is ongoing, and both the exhibition and film embody this slow, often painful process of healing.

Exhibiting Forgiveness transcends the boundaries of art and film, offering a raw and poignant exploration of familial relationships, generational trauma, and the complex path toward healing. Through his art, Kaphar invites viewers to confront their own absences, wounds, and hopes for reconciliation.